North America | Alaska

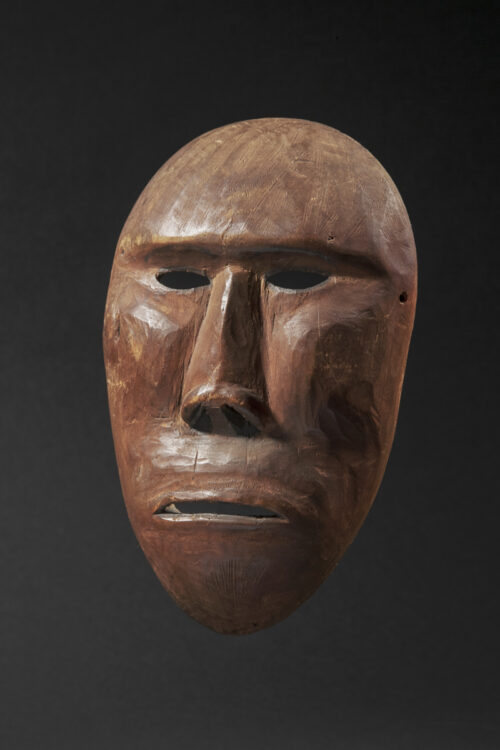

Yup’ik Mask

Alaska

Seal Spirit Mask

Yup’ik Eskimo

Norton Bay, Saint Michael, Alaska

Late 19th century

Carved wood, hide, pigments

Height: 25 cm – 10 in.

Provenance

Collection Merton Simpson (1928-2013), New York

Collection Tony Berlant, Santa Monica,California

Collection Michel Van Den Dries, Gavere, Belgium

Collection David Utzon-Frank, Copenhagen

Yup'ik Mask Seal Box/ Galerie FLAK

Price: on request

As noted by the Barbier-Mueller Museum, which holds a mask of the same type, abstraction appears to be the most appropriate term to describe these masks attributed to the so-called “Master of the Seal Box,” whose simplicity rivals their beauty. This creator is recognized for the distinctive and highly original style applied to each of his works. The identification of a “signature” is rare and delicate in the context of cultures foreign to the Western notion of “art history,” whose material production was, until recently, approached solely through the lens of ethnology.

The corpus of the “Master of the Seal Box” includes several closely related masks. The upper part of the mask’s structure, box-shaped in form, presents an extremely stylized human face: two large oval cavities indicate the eyes, while the ridge of the nose is suggested by a slender protuberance.

A rather realistic seal’s head projects from the base of the mask, forming a kind of handle.

This type of mask was used in ritualized performances during which humans entered into communication with animal spirits, exhorting them to meet their needs by providing abundant game.

It is said that the spirit of the animal (yua or inua in the Yup’ik language) resided within the container—or box—of the geometric upper portion of the mask.

According to Eskimo beliefs, it was the souls of animals that chose to offer their bodies to humans, thus determining periods of abundance or famine. Humans were therefore required to observe a number of prescriptions governing their subsistence activities in order to secure the benevolent cooperation of animal souls. While the animal’s body was consumed, its spirit, by contrast, never died.

On the reverse of the mask, the eyes are highlighted with red pigment. Viewed from this angle, the mask recalls the head of a bird, with the carved seal at the lower part forming the beak.

This mask is distinguished by its poetic resonance and the purity of its forms.

The corpus of the “Master of the Seal Box” includes several closely related masks. The upper part of the mask’s structure, box-shaped in form, presents an extremely stylized human face: two large oval cavities indicate the eyes, while the ridge of the nose is suggested by a slender protuberance.

A rather realistic seal’s head projects from the base of the mask, forming a kind of handle.

This type of mask was used in ritualized performances during which humans entered into communication with animal spirits, exhorting them to meet their needs by providing abundant game.

It is said that the spirit of the animal (yua or inua in the Yup’ik language) resided within the container—or box—of the geometric upper portion of the mask.

According to Eskimo beliefs, it was the souls of animals that chose to offer their bodies to humans, thus determining periods of abundance or famine. Humans were therefore required to observe a number of prescriptions governing their subsistence activities in order to secure the benevolent cooperation of animal souls. While the animal’s body was consumed, its spirit, by contrast, never died.

On the reverse of the mask, the eyes are highlighted with red pigment. Viewed from this angle, the mask recalls the head of a bird, with the carved seal at the lower part forming the beak.

This mask is distinguished by its poetic resonance and the purity of its forms.

Explore the entire collection